Target audience

Research and Administrative Staff: Curators, Marketing and Communications Staff, Researchers, Conservators and others

IT Staff: Developers, Database managers, IT managers, Designers

Contextualization of Digitization

A very brief historical context of Digitization in Museums

To understand current digital content in museums we need to look at the history of digitization in the museum context. The digitization of cultural collections can be dated back to projects such as Corpus Thomisticum by Robert Busa SJ and associates initiated in 1949 in cooperation with IBM digitizing the complete works of St Thomas Aquinas [Norman, 2022]. The discourse on digitization in museums started in the early 1970s and the British Museum digitization of their collection and records began in 1979. Robert G. Chenhall and Peter Homulos wrote in 1978 ‘Very few museums have ever had completely adequate records of the objects in their collections. Most try to maintain some account of new accessions, either in bound ledgers or on cards, and individual curators often keep files that are more or less adequate for their own research, if used in conjunction with a good memory. But, except for the records necessary to provide legal accountability, most collection documentation can be said to be non-systematic. [...]’ [Chenhall and Homulos, 1978]

Historically, information about objects were stored in physical ledgers, on cards, in inventory books or in files with photographs, letters, sale receipts, exhibition materials and others. In the end of the 1960s large digitization projects started to systematically document these information with computer technology, meaning that the material was transcribed, scanned and photographed. Consequently these materials were stored in databases following a systematic logic conceptualizing database standards and data formatting. As early as 1969, a consortium of 25 US art museums called the Museum Computer Network (MCN) and its commercial partner IBM declared, “We must create a single information system which embraces all museum holdings in the United States” [Waibel, 2010] . Approaches of standardization for metadata and vocabularies was first introduced in 1969 with the intention to make data shareable, transferable, linkable and grant easy access and retrievable information across museum databases. However, since the beginning of digitization, museums also followed their own, individual logic for cataloging information and consequently many data authorities were produced. This has been documented well in literature [e.g. Turner, 2020] and Lincoln pointed out for today’s data reality in museums internationally, ‘there are several relevant authorities out there […] VIAF, LOC subject headings, DBpedia, GeoNames, not to mention the Getty’s AAT, ULAN, and TGN. The British Museum links to none of them. […] They already have their own internal thesaurus of people and materials and subjects, and to map those to existing authorities would be a monumental task’ [Lincoln, 2016].

[Example of an early digitisation program to bring diverse data into a joined database in 1978 [Sher, 1978, p. 154]

Digitization of data in museums has a long standing history and since its beginning museum staff were interested in reflecting on the data that is produced by museums, to use data in their own research on objects, to communicate data to an interested audience and to connect data to information outside of the museum’s collection.

To summarize, digitization is the process of converting information into a digital format and to create digital documentation or digitally born information. In the context of museum collections that means that information that were historically stored and collected prior to working with the computer on catalog cards or curator notes were being converted into a digital format such as “structured” data, digital photographs or scans, sound, and other digital documentation. It also means that today that information is created in digital formats. This digital material is stored in databases that traditionally resembled the information that one could find on index cards, which has also gradually changed over time and today’s databases are developed according to digitally born information, relationships between these information and is strongly related to the current or even temporary interests and technologies and needs of the museum. Databases are dynamic, they can change over time in the same way museum collections can change over time.

Goal

The goal of this blog text is to familiarize museum staff who are using and producing data with current standards, competences, literature and use cases. How do museums produce their data? How do museums store data internally and present their data to the public? Internationally there is not one standard for meta-data frameworks or data in museums but rather there are many. Some museums are referencing standards in their data production, some museums are writing their data to the immediate need of the person using the database. Before starting a digital project or a digitization project in the museum context this text provides critical information about infrastructure, vocabularies, meta-data frameworks and links to sources with further information. The goal is to give an overview of these resources so museum staff can make informed decisions about their data collection and production.

Understanding terms: Finding a common language

Prior to starting a new digital project or digitization efforts in a team or institution, it is important that certain ambiguous terms are clarified before starting a project. Below is a short overview of starting points for clarifications on these terms. Because of their ambiguous nature, they can be understood differently depending on the context and this is the discussion that needs to take place in the team, so referencing these terms make sense to the individual project.

Data

The term “data” is an ambiguous term. Digital data in the museum context can be described close to Christine Borgman’s definition: “In addition to digital manifestations [...], it refers to forms [...] that generally require the assistance of computational machinery and software in order to be useful, either generated or compiled, by humans or machines [Borgman, 2015].”

An example for this abstract definition in the museum context could be an object, which can be described as data (or display data), especially when it comes to digitally born objects. Below is an example that defines the object as the material that data is collected about. This is typically found in online catalogs:

Data that museums most commonly produce are Audio, Images, Text, Video and Web formats as information and documentation (data values) about the objects in their collections. It is important to clarify amongst museum practitioners which term they are using to describe the information about an object (data) and about the data values or information (meta-data). Below is a list of data formats that museums produce and these data are usually stored in a database that internal staff has access to:

Text-based: .txt, .xml, .rtf, .odt

Image-based: .tif/tiff, .jpeg, .png

Audio-based: .mp3; .wav

Video-based: .avi, .mov, .mp4, .wmv

Web-based: .htm, .xhtml, .js, .xml.

In the example above the image that we are viewing is not the object (unless it is a digitally born artwork) but rather image-based data that is stored as documentation of the physical object in the database. Often digital images are described in object-referencing terms but it needs to be clear in the documentation if the person producing the data is referencing information about the digital image (as data) or the physical object.

Meta-data

Meta-data is information about data. Meta-data gives information about the data values in a database, it describes the information that are found in a particular field. This can also be called field titles or meta-data titles. Meta-data can also refer to data that gives information about digital images, which are already data values in the documentation process. It is important to clarify the meta-level when using the terms data and meta-data.

Databases

Databases in museums vary from institution to institution. Databases are not only places to store information about objects but also about operations in the museum related to objects such as, storage, restoration, loans, etc. or information about images and other information that are relevant for staff in the museum. Databases can be powerful tools when used in a way that allows the machine to interact and retrieve data in human interactions. It is not possible for most databases to retrieve data in natural language processes and therefore it is important to understand limitations and possibilities of human-machine interactions for the best results in data retrieval and information storage. That means in clear words, the more care an institution has for data production and the clearer it is for staff how computers interact with human-made information the better a database will work as an information tool.

We can describe the purpose for databases as the following ways:

Documenting collections (data about the object's materials, dates, creator, etc.)

Managing collections (information about rights, access, use, location control, etc.)

Resource discovery (information used to find and identify digital or physical resources)

Preservation

Please make sure before you are starting a project to clarify the terms

collection management system referred to as CMS

content management system also referred to as CMS but often used in web development as a software tool to manage the creation and publication of digital content

digital asset management system or DAMs, which sometimes is interchangeably used with collection management systems and sometimes used to differentiate between a database on digital assets of the institution and the digital information about the collection. DAMs also often refer to databases that store digital media, such as large image files and in some institutions this database is separated from information that is stored by research teams, curators or collection managers about objects.

Often institutions only have one database which is referred to as collection management system, collection database, or digital asset management system. However it is important to clarify these terms with your institution and understand where, how and which information are stored and preserved. Here the list of values that are typically stored and preserved or communicated in the institutions’ collection management systems

“Documenting collections

Catalog description: Information that describes and identifies objects, including creator/maker/artist, date(s) of creation, place of creation, provenance, object history, research on the object, and connections to other objects.

Preservation

Conservation management: The management of information about an object's conservation “from a curatorial and collections management perspective," including conservation requests, examination records, condition reports, records of preventative actions, and treatment histories.

Risk management: Management of information about potential threats to collections objects, including documentation of specific threats, records of preventative measures, disaster plans and procedures, and emergency contacts.

Managing collections

Object entry: Managing and documenting information and tasks related to objects entering the museum, including acquisition or loan records, receipts, record of the reason for the deposit of the object, and record of the object's return to its owner.

Acquisition: The management and documentation of objects added to the institution's collection, including accession numbers, catalog numbers, object name or title, acquisition date, acquisition method, and transfer of title. There are many different accession numbering systems, and a CMS should allow an institution to use its existing numbering system.

Inventory control: Identification of objects for which the institution has a legal responsibility, including loaned objects and objects that have not been accessioned. Information recorded includes object location and status.

Location and movement control: Records of an object's current and past locations within the institution's premises so that it can be located, including dates of movement and authorizations for movement.

Insurance management and valuation control: Documentation of insurance needs for objects for which the institution is responsible (included loaned objects) as well as the monetary value of objects for insurance purposes. This may include the names and contact information of appraisers as well as appraisal history.

Exhibition management: Management of an object's exhibition or display, including exhibition history and documentation of research done on an object for an exhibition. More advanced Collections Management Systems may have the ability to present information from the system on a museum's website or in an online exhibit.

Dispatch/shipping/transport: Management of objects leaving the institution's premises and being transferred to a different location, including location information, packing notes, crate dimensions, authorizations, customs information and documenting the means of transportation (including courier information).

Loaning and borrowing: Managing the temporary transfer of responsibility of an object from the museum to another institution or vice versa, including loan agreements, loan history, records of costs and payments, packing lists, and records of overdue loans.

Deaccessioning and disposal: Management and documentation of objects being deaccessioned and leaving the institution's collection, either by transfer, sale, exchange, or destruction/loss, including transfer of title, records of approval, and reason for disposal.”

Please refer to the wikipedia page on Collection Management Systems, where this information is retrieved from and pay close attention to their bibliography that is constantly growing: Wikipedia Collection Management System

To summarize data is information to describe, document and preserve information about an object (digital, material or immaterial) and the life of this object in and outside of the museum. Meta-data is the category or field that this information is stored under. It gives the user of a database information about the values that are stored in the database. Information that have a common set of meta-data (fields) are stored in a database. Databases in museums vary in data and meta-data standards depending on the needs of the institution.

Guidelines

The following guidelines are created as resources for museum staff to produce data about their collections. The guidelines are basic principles that need to be expanded on in an internal discussion in the institutions to find best practices that fit the needs of each individual institution or digital project.

Data Management

Who is interacting with data and what are their needs?

Curators, Conservators, Researchers, Collection Managers, Storage and Operations managers, Developers, Communications and Marketing staff or IT staff are all using and producing data in the collection management system or the database that allows to store information about objects and operation. In some institutions different roles have different access to content and content production.

It is important to understand the needs of the research and administration side as well as the technology side of data production. Research and administration staff might use fields as free text fields to store notes and information that they would like to communicate internally. Rather than storing data in a way that is only machine readable the IT staff can build both fields for an easy data retrieval and also free text fields. Research and administration staff are likely to build a work-around in the database if the limitations in data production are too strongly related to IT needs. A balance between the technical needs and the researchers' needs in using data as information for human interaction and machine (computer) interaction is advisable. Strategies for this balance depend on the data management system that is used and on the skill sets and staffing in the institution. A course in using standardized data for some fields (names, geo locations, measurements, dates, image files, material, bibliographies, indexing such as Object IDs etc.) and free text for certain others (research and curator notes, descriptions, provenance) is a balance that is recommended here. Provenance data has been suggested to be standardized by the Art Tracks project at the CMOA (https://cmoa.org/art/art-tracks-digital-provenance-project/), however it depends on the context of the data, as it is easier for audiences online to read a full text, rather than computer readable data.

Below are resources and overviews for Data Management Systems, data and meta-data standards that are the foundations to make decisions that consider researchers and administrators in a balance with IT staff in museums:

Data Management Systems

These are some of the most common data management systems that museums currently use internationally. They provide the museum with a data infrastructure for data storage, information and document retrieval and publishing or distribution of data.

The following interactions need to be considered when building a CMS in the museum context.

Indexing

An index number is a unique identifier that is given to each object that is described in the collection management system. It is unique to an object or object collection, which are objects that are part of a larger body with multiple parts. The ID number follows an internal logic and corresponds to ID numbers in other CMS in the institution such as storage and photographic databases. One of the most common mistakes that are made is that special characters in these IDs are not consistent when referring to documentation material that belongs to this object. It is important that the unique ID matches across all CMS for example in the file name of digital images, videos or storage numbers. An index topology or scheme is chosen by the institution and it is of critical importance that it is followed including special characters such as dots and dashes.

Data validation

In order to retrieve information data standards and controlled vocabularies are a great starting point for data production and documentation.

Metadata standards generally have the following objectives:

promoting consistency within and between databases

facilitating exchange of information between databases

facilitating the migration of data to new systems

Data standards generally have the following objectives:

enhancing information retrieval (particularly, automated retrieval)

ensuring that important information is recorded in a way that allows other users to understand it and make connections

Source: (Network, 2019)

Museums internationally are currently using differing standards in formatting and structuring meta-data documentation. The following links show some of the most common meta-data and data standards:

Meta-data Standards:

Data Standards:

The Info-Muse classification system for ethnology, history and historical archaeology museums

The Info-Muse classification system for fine arts and decorative arts museums

Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging

Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT) Objects Facet

Cultural Objects Name Authority (CONA)

Religious objects - user's guide and terminology

Vocabulary of Basic Terms for Cataloguing Costume

British Museum Object Names Thesaurus

Liste des dénominations, Service des musées de France

Thesaurus for Graphic Materials II: Genre and Physical Characteristic Terms (TGM II)

Forum on Information Standards in Heritage (FISH) Archaeological Objects Thesaurus

Resources under this link: CHIN Guide to Museum Standards

Certain words are not appropriate to use because they are offensive, outdated, derogatory, racialised or otherwise inappropriate. It is important to mark and find a solution for the display of such data when digitizing historical documents. Please familiarize yourself with these vocabularies and avoid the use and publishing of the following words:

Words Matter: https://www.tropenmuseum.nl/en/about-tropenmuseum/words-matter-publication

List of ethinic slurs: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ethnic_slurs

List of offensive words: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~biglou/resources/

Racial Slur database: http://www.rsdb.org/full

For a broader context on how cataloging practices in the museum context are embedded in colonial histories please familiarize yourself with Cataloging culture. Legacies of Colonialism in Museum Documentation by Hannah Turner (2020).

Storage

It needs to be clearly documented where digital materials are stored and under which hierarchical storage management system. Some institutions store images and data in the same system, some use linked and relational databases with different access restrictions. This workflow needs to be clearly indicated by the institution.

Retrieval

The choice of CMS for an institution is also dependent on the type of queries that it allows and the specific formats it allows for data retrieval and exports. It is important to speak about the needs of the institution’s staff before the development and choice of a specific CMS.

Distribution

The main difference in distribution about information and documents stored in databases is the internal and external distribution of information.

Internal distribution: Access levels and data production need to be defined. Who can access, change and write data needs clear definitions.

External distribution: Online databases of museums seldomly give access to all internally stored information and the externally distributed information is vetted, curated and selected for publication. Licenses and copyrights, resolutions and meta-data fields need to be defined for the external distribution.

Data Publishing

Online catalogs

Institutions are now moving to systems that allow them to push data about their collections online in a curated and updated method. Internal databases of a museum and the online collection database of a museum can entail different data dependending on the level of editing, curation and staff that works, edits, cleans or vets information before they are published online. Some museums show their data in view only online catalogs and some are publishing their data as open data, which means that the data is already available and presented in a way that allows a human-machine interaction. Most of the time this means that data is packaged in json or xml formats. A standard that was pushed by ICOM for describing museum objects is LIDO. However when choosing a schema to publish open data LIDO is not used by most museums and is not easy for most developers to reuse.

Publishing data online is also bound to certain licenses and copyrights that institutions have for their images and other digital materials. For referencing differing online sources, licenses and copyright policies and practices please consult the following survey of online GLAM (an acronym for galleries, libraries, archives, and museums) data that shows the access policies and practice of over 700 institutions worldwide since 2018 to the present. It was initiated by Douglas McCarthy and Dr. Andrea Wallace is still an active and growing list. Making data in the museum's context accessible can differ from country to country and an international comparison of these practices might be interesting to explore in this survey before starting a conversation in the institution internally. Publishing data, images and digital materials online should also be placed under considerations of an ethical distribution of information. Can this data harm a community or people because it misrepresents information or leaves certain perspectives, languages and knowledges out. Who should decide what is published about cultural expressions? This question is incredibly important to ask when considering whether to publish digital materials in the public domain, which means that no copyright applies to the digital material, which allows any adaptation and commercial use of the digital material. This is an important consideration when bringing images of original cultural expressions (e.g. patterns on objects, voices, songs etc) that originate in a particular cultural context and were not meant to be distributed on large scale or for commercial use of for example large fashion companies. Resources to start a conversation in this direction are for example the Open Restitution Africa Podcast series asking questions on access, purposes and decision making processes “about digitisation that ensure these objectives are met in ethical, equitable ways” [Open Restitution Africa, 2022] and a reflection on copyright and related issues [Oriakhogba, 2022] referencing Digital Benin, a digital platform that brings together data on over 5000 historic objects from the Kingdom of Benin in 131 institutions worldwide.

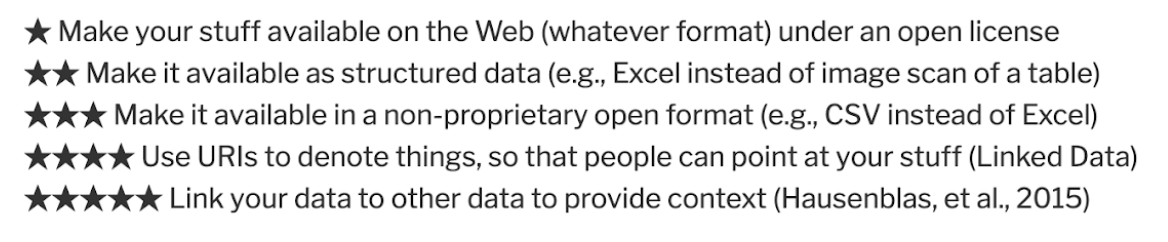

Publishing Data Online: 5 star considerations

When publishing data online general considerations that are made for information sharing, distribution and interoperability can also be applied in the museum context. Below are some examples to contextualize the “Five Stars of Open Data” developed by Sir Tim-Berners Lee, founder of the World Wide Web.

Luther, Anne, Neely, Liz, and Weinard, Chad. "Cultural Collections as Data: Aiming for Digital Data Literacy and Tool Development." MW19: MW 2019. Published February 1, 2019.

One Star describes most online catalogs on museum websites because the data that is published on websites of museums in online catalogs often only allows a read only access. This means that the user can only access information similar to a book, it can not be downloaded or retrieved in an automated way. Information can be looked at, transcribed, or manually copied. The online catalog is a reference tool that shows copyright restrictions and licenses for the data displayed.

Two stars describes data publishing as structured data in excel files, including images and other digital material.

Three stars describe all of the above and data that is made accessible in repositories with data that is parsed into manageable files that have clear structures. This data might be relational data and could also be accessible in APIs . APIs give access to data for a public with programming skills or to internal development staff, depending on the access that is granted by the institutions.

Four stars describe an active community in the museum context - Linked-Open Data.

An active LOD community in museums are working on releasing museum data under an open license to central storage repositories such as wikiData and Getty Research Institute which are major data sources in the museum context.

5 stars can be described as connections that an institutions makes to a larger context outside of the GLAM context. One example of this is The Met and its initiative to publish “375,000 images of public domain art freely available under Creative Commons Zero on Wikimedia. [Knipel, 2017]” One of these images is the work The Adoration of the Christ Child by the School of Jan Joest (circa 1450-1519) embedded in the Wikipedia entry “Down syndrome”. The Wikipedia entry is referencing an article in the American Journal of Medical Genetics by Levitas and Reid [doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.10043] suggesting that this Early Netherlandish painting is one of the earliest depictions of a person with Down syndrome. The data source of this image that is linked on the media repository of wikipedia is the online catalog entry of this object of The Met, which shows full object details, provenance, exhibition history, references and more. The contextualization made this image at some point the most viewed image by unique users from an outside source in the online catalog on The Met’s website. The contextualization drives traffic directly to the museum's website. [see Luther, Anne, Neely, Liz, and Weinard, Chad. "Cultural Collections as Data: Aiming for Digital Data Literacy and Tool Development." MW19: MW 2019. Published February 1, 2019.]

For further resources on publishing data online please consult the research consortium Collections as Data’s website: https://collectionsasdata.github.io/. The site also shows resources and methods to start conversations about collections as data in institutions and how to lobby for this important conversation internally.

Licensing

The first step to work with the most appropriate licenses is a familiarization with the creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/about/cclicenses/ For cultural expressions it is necessary to ask who the owner, maker or producer of the content is that is being documented. For historic objects that are not emerging from the art context or that do not have a clear artist/marker documented, it is often not considered that patterns, knowledge and expressions go beyond objects that are considered “Art” and copyrights differ in national contexts.

Summary

The production of data is dependent on the needs and resources of an institution, and guides for writing, storing and publishing data are made available in this tool kit. Before starting to update or work on new digital projects recommendations, resources and short considerations in this document can be a starting point for a closer look at the way institutions are currently storing and producing data. To identify best practices on sharing and access to information in your institution, this tool kit is a starting point to find a common language, reference existing practices and consider the needs of data producers in the museum context.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Borgman, C. L. (2015). Big data, little data, no data: scholarship in the networked world. The MIT Press.

Chenhall, R. G., & Homulos, P. (1978). Museum data standards. Museum International, 30(3–4), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0033.1978.tb02138.x

Knipel, R. (2017). The Metropolitan Museum of Art makes 375,000 images of public domain art freely available under Creative Commons Zero. Diff. https://diff.wikimedia.org/2017/02/07/the-met-public-art-creative-commons/

Lincoln, M. D. (2016). Linked Open Realities: The Joys and Pains of Using LOD for Research. https://matthewlincoln.net/2016/06/06/linked-open-realities-the-joys-and-pains-of-using-lod-for-research.html

Luther, A., Weinard, C., & Neely, L. (2019). Cultural Collections as Data: Aiming for Digital Data Literacy and Tool Development. MW19 | Boston. https://www.academia.edu/38278177/Cultural_Collections_as_Data_Aiming_for_Digital_Data_Literacy_and_Tool_Development

Norman, J. (2022). Roberto Busa & IBM Adapt Punched Card Tabulating to Sort Words in a Literary Text: The Origins of Humanities Computing. History of Information. https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=1959

Open Restitution Africa. (2022). Access for Who? Open Restitution Africa. https://openrestitution.africa/resources/podcast/

Oriakhogba, D. O. (2022). Repatriation of ancient Benin bronzes to Nigeria: reflection on copyright and related issues. Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, jpac089. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiplp/jpac089

Waibel, G., LeVan, R., & Washburn, B. (2010). Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to Share. D-Lib Magazine, 16(3/4). https://doi.org/10.1045/march2010-waibel

Further Reading:

Atairu, M. (2021). Benin Bronze Tracker – Benin Bronze Tracker. http://beninbronzetracker.minneatairu.com/

Borgman, C. L. (2015). Big data, little data, no data: scholarship in the networked world. The MIT Press.

Bowrey, K., & Anderson, J. (2009). The Politics of Global Information Sharing: Whose Cultural Agendas Are Being Advanced? Social & Legal Studies, 18(4), 479–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663909345095

Brown, K. (Ed.). (2020). The Routledge Companion to Digital Humanities and Art History. Routledge.

Burdick, A. (Ed.). (2012). Digital Humanities. MIT Press.

Cameron, F., & Kenderdine, S. (Eds.). (2010). Theorizing digital cultural heritage: a critical discourse. MIT Press.

Ceci, L. (2022). Mobile internet usage worldwide. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/779/mobile-internet/

Chander, A., & Sunder, M. (2004). The Romance of the Public Domain. California Law Review, 92(5), 1331. https://doi.org/10.2307/3481419

Christen, K. (2009). Access and Accountability: The Ecology of Information Sharing in the Digital Age. Anthropology News, 50(4), 4–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-3502.2009.50404.x

Christen, K., & Anderson, J. (2019). Toward slow archives. Archival Science, 19(2), 87–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-019-09307-x

D’Ignazio, C., Klein, L. F., & Schnaubelt, T. (2020). Data Feminism. The MIT Press.

Douglas, S., & Hayes, M. (2019). Giving Diligence Its Due: Accessing Digital Images in Indigenous Repatriation Efforts. Heritage, 2(2), 1260–1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2020081

German Contact Point for Collections from Colonial Contexts: Benin-Bronzes in Germany. (2021). https://www.cp3c.org/benin-bronzes/

Gilbert, P. (2022). Nigerian Internet and mobile penetration grows. Connecting Africa. http://www.connectingafrica.com/author.asp?section_id=761&doc_id=767400

Groĭs, B. (2021). Logic of the collection. Sternberg Press.

Hooland, S. van, & Verborgh, R. (2014). Linked data for libraries, archives and museums: how to clean, link and publish your metadata. Facet Publishing.

Janke, T. (1998). Our Culture: Our Future – Report on Australian Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights. AIATSIS. https://www.terrijanke.com.au/our-culture-our-future

Katyal, S. K. (2017). Technoheritage. California Law Review, 105(4), 1111–1172. https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38PN8XF0T

Krabbe Meyer, M. K., & Odumosu, T. (2020). One-Eyed Archive: Metadata Reflections on the USVI Photographic Collections at The Royal Danish Library. Digital Culture & Society, 6(2), 35–62. https://doi.org/10.14361/dcs-2020-0204

Langmead, A., Berg-Fulton, T., Lombardi, T., Newbury, D., & Nygren, C. (2018). A ROLE-BASED MODEL FOR SUCCESSFUL COLLABORATION IN DIGITAL ART HISTORY. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR DIGITAL ART HISTORY, No. 3.

Lixinski, L. (2020). Digital Heritage Surrogates, Decolonization, and International Law: Restitution, Control, and the Creation of Value as Reparations and Emancipation. Santander Art and Culture Law Review, 2 (6), 65–86. https://doi.org/10.4467/2450050XSNR.20.011.13014

Lóscio, B. F., Burle, C., & Calegari, N. (2017). Data on the Web Best Practices. https://www.w3.org/TR/dwbp/

Loukissas, Y. A. (2019). All Data Are Local: Thinking Critically in a Data-Driven Society. The MIT Press. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/servlet/opac?bknumber=8709328

Luther, A., Neely, L., & Weinard, C. (2019). Cultural Collections as Data: Aiming for Digital Data Literacy and Tool Development – MW19 | Boston. https://mw19.mwconf.org/proposal/cultural-collections-as-data-aiming-for-digital-data-literacy-and-tool-development/index.html

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: how search engines reinforce racism. New York University Press.

Odumosu, T. (2020). The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons. Current Anthropology, 61(S22), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1086/710062

Pavis, M., & Wallace, A. (2019). Response to the 2018 Sarr-Savoy Report: Statement on Intellectual Property Rights and Open Access relevant to the digitization and restitution of African Cultural Heritage and associated materials. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.2620597

Pavis, M., & Wallace, A. (2020). SCuLE Response for the EMRIP Report on repatriation of ceremonial objects and human remains under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.3760293

Pendergrass, K. L., Sampson, W., Walsh, T., & Alagna, L. (2019). Toward Environmentally Sustainable Digital Preservation. The American Archivist, 82(1), 165–206. https://doi.org/10.17723/0360-9081-82.1.165

Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group. (2019). CARE Principles of Indigenous Data Governance. The Global Indigenous Data Alliance. https://www.gida-global.org/care

Risam, R. (2019). New digital worlds: postcolonial digital humanities in theory, praxis, and pedagogy. Northwestern University Press.

Sher, J. A. (1978). The use of computers in museums:present situation and problems. Museum International, XXX(n° 3/4), 132–138, illus. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000127275

Survey of GLAM open access policy and practice (Douglas McCarthy and Dr. Andrea Wallace, CC BY 4.0, 2018 to present). (2018). Google Docs. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/u/1/d/1WPS-KJptUJ-o8SXtg00llcxq0IKJu8eO6Ege_GrLaNc/edit?usp=embed_facebook&usp=embed_facebook

Thylstrup, N. B. (2018). The politics of mass digitization. The MIT Press.

Turner, H. (2015). Decolonizing Ethnographic Documentation: A Critical History of the Early Museum Catalogs at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, 53(5–6), 658–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2015.1010112

Turner, H. (2020). Cataloguing culture: legacies of colonialism in museum documentation. UBC Press.

Waibel, G., LeVan, R. R., & Washburn, B., OCLC Research. (2010a). Museum data exchange: learning how to share : final report to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. http://www.oclc.org/research/publications/library/2010/2010-02.pdf

Waibel, G., LeVan, R., & Washburn, B. (2010b). Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to Share. D-Lib Magazine, 16(3/4). https://doi.org/10.1045/march2010-waibel

Wallace, A. (2021). Decolonization and Indigenization. Open GLAM. https://openglam.pubpub.org/pub/decolonization/release/1

Walter, M., Kukutai, T., Carroll, S. R., & Rodriguez-Lonebear, D. (2020). Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Policy (M. Walter, T. Kukutai, S. R. Carroll, & D. Rodriguez-Lonebear, Eds.; 1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429273957